From a pure baseball perspective, Opening Day doesn’t matter very much. In fact, compared to other pro sports, it matters the least. The first game constitutes exactly 0.6 percent of the schedule. Last season, The Boston Red Sox and Los Angeles Dodgers were 0-1 and wound up in the World Series.

So our brains tell us that Opening Day doesn’t matter much at all. Our hearts disagree passionately. Why? Why does Opening Day stir such excitement, such pure happiness?

Don’t worry, I’m not going to go all “Baseball as the Meaning of Life” on you here. Baseball is not life. It’s just a sport. Young men playing a child’s game.

And yet … and yet …

Opening Day does matter. It matters more to me, in fact, as I grow older and my fandom runs deeper, and I appreciate the fact that a multitude of Opening Days stirred millions of people before I was born and will do the same long after my final season. I delight in Opening Day much the way I do in Christmas Eve or … actually, it’s just those two days, the best two days of the year.

I think the answer lies deeper than the venerable “hope springs eternal” phrase, or the standard metaphors about rebirth and rejuvenation, although elements of all of that are true. I wonder if the answer is this: Opening Day brings a unique trio of anticipation — a desire for stability, an expectation of sobering reality, and a yearning for youth.

Let me explain, one at a time.

Stability

Opening Day is a sure thing. Despite the always-changing nature of the game, we know that on Opening Day the most talented players in the world will take the field of this beautiful game and play it, more or less, the same way it has been played all of our lifetime — and the lifetime before that. As sure as the dew forms and fades on the outfield grass every morning, we can count on Opening Day. There’s not much else in the world so reliable as the SAMENESS of a new season. Poet Donald Hall, a big baseball fan, wrote about it … poetically:

“In the country of baseball, time is the air we breathe, and the wind swirls us backward and forward, until we seem so reckoned in time and seasons that all time and all seasons become the same.”

At a time when our faith in our institutions and leaders seems to continue to erode, you can still place faith in a baseball season. Rules change, but the fundamental pitch-by-pitch dynamic is essentially the same as 90 years ago. Players and financials change, but your filled-in scorebook looks the same. Teams may be “tanking” and analytics driving change, but a box score still remains the ultimate in efficient data storytelling, just like it was 20 or 40 or 80 years ago. We long for that stability, that routine, that normalcy we find so infrequently in the real world. It all returns on Opening Day.

Reality

Running on that current of stability is a harshness of reality baseball brings, and as we get older we acknowledge and even welcome it, as opposed to getting frustrated by it. Baseball stamps that on our hearts each season, each week, each game. Others have written that baseball teaches us a lot about failure. We know that each team will celebrate at least 50 times (well, maybe not the Orioles) and walk off dejected 50 times, for sure, each year. Most likely,, those minimums are 70 wins and 70 losses (well, maybe not the Astros).

This reality of losing, of failure, is unique to baseball. In the NFL, losing or winning just a game or two each season is quite possible. In the NBA, a few teams finish above .700 every season, sometimes even .800.

But in baseball, only a handful of teams have won 7 of every 10 games over the course of a season. You have to go 114-48 to do that. We know, on Opening Day, that 1-0 will not result in 114 wins. And that the hitter who goes 4 for 4 will, in the end, not hit .400. Because baseball is hard. Success is fleeting (well maybe not for Mike Trout) and on Opening Day comes not just the excitement but the anticipation of the long grind to come, of the 185,000 league-wide regular-season plate appearances, most of those ending in an out.

This sobering reality is what we also love about Opening Day. Baseball delivers a hard slider of failure and imperfection season by season, game by game, pitch by pitch.

Yearning for Youth

When we were 9, we knew nothing of that reality. All the world was a glistening diamond and crisp uniforms and bubble gum, and anything was possible on Opening Day. How often do we feel that in life? I do, on Opening Day.

This special moment that occurs just once a year: the possibility that no matter how poor your team is, 1-0 is achievable. Besides clinching a playoff berth on some September night, is there a single moment in the entire season that’s more satisfying for a fan than 1-0? On Thursday, the Orioles (the worst team in baseball) will play the Yankees (one of the best). And unlikely as it may seem, Baltimore does have a chance to be 1-0, to be ahead of the Yankees, if only for a day or so.

1-0 is powerful. Barring rainouts, 14 teams will be 1-0, and for fans of those teams the world will be a little lighter, the air, however faintly, will smell like freshly-mowed grass. And optimism will reign, at least until the next game, when chances are 1-0 will be replaced by 1-1.

This Thursday is Opening Day! No, baseball is not life. But the sport, with daily lessons on failure mixed with occasional glorious moments, certainly does as good a job as anything else reflecting these aspects of our existence.

Enjoy the return of the routine and sobering reality, and revel in the youthful excitement of this Opening Day. And may you wake up Friday morning 1-0.

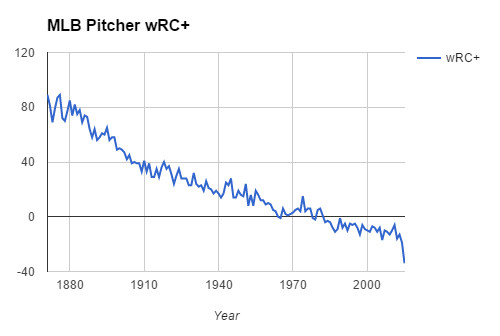

*** Pitcher at the plate: Guess what kind of chance he has with this stance?

*** Pitcher at the plate: Guess what kind of chance he has with this stance?

Camden Yards this past May. Just think how many empty seats this month.

Camden Yards this past May. Just think how many empty seats this month.

Generally speaking, the most passionate baseball fans were baseball fans in their youth. A parent or coach (who were most likely baseball fans in their youth) explained the game, taught it, watched it, nurturing the young fan like a gardener tending a new floral bed. Though I have no scientific data to back this up, I strongly believe that baseball fandom is most easily attained as a kid; harder, compared to other sports, to develop a deep love for the game when starting out as an adult.

Generally speaking, the most passionate baseball fans were baseball fans in their youth. A parent or coach (who were most likely baseball fans in their youth) explained the game, taught it, watched it, nurturing the young fan like a gardener tending a new floral bed. Though I have no scientific data to back this up, I strongly believe that baseball fandom is most easily attained as a kid; harder, compared to other sports, to develop a deep love for the game when starting out as an adult.